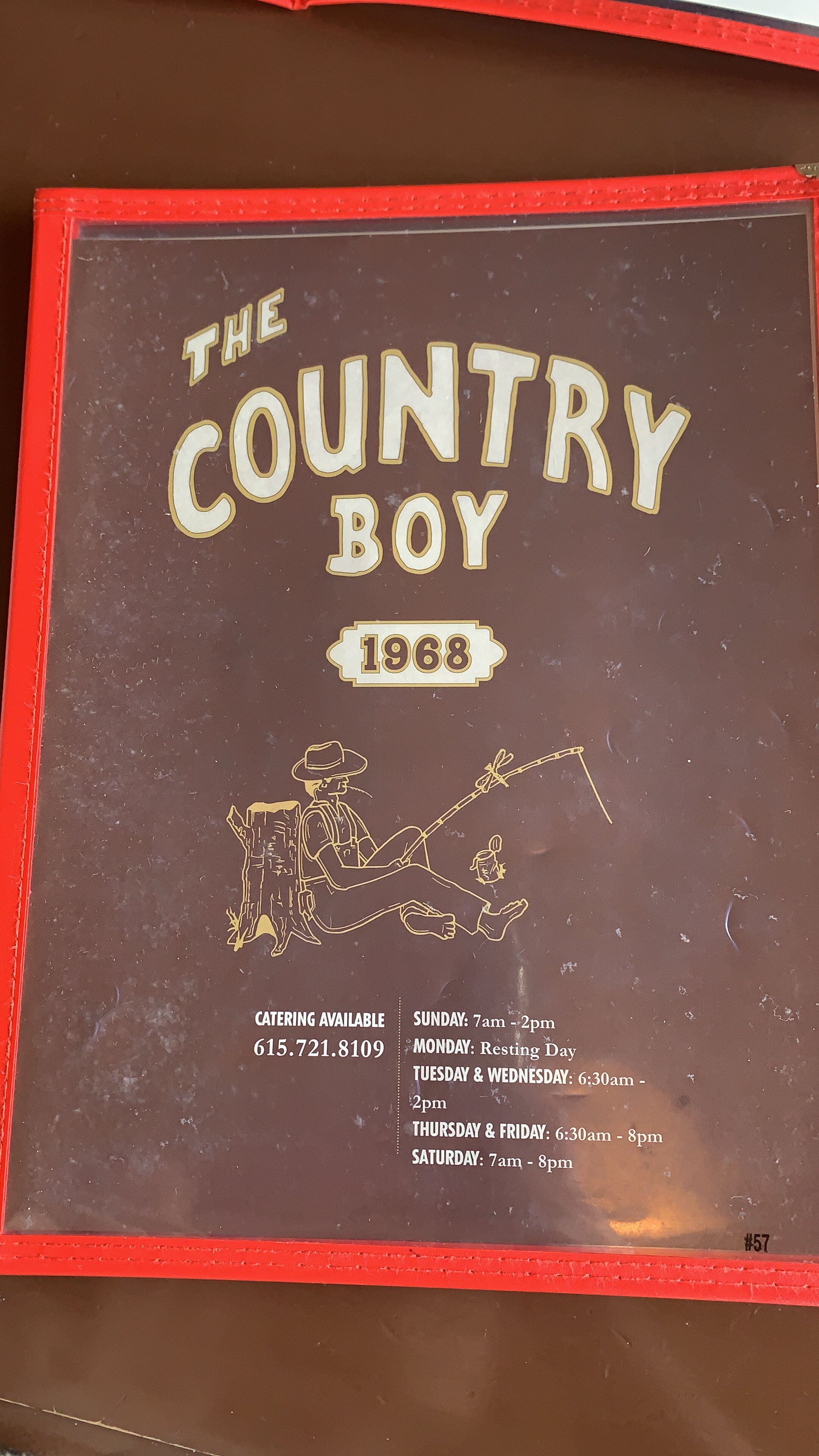

The Country Boy

We could have been at any of Nashville’s finest lunch spots in a matter of minutes. We have plenty of favorites—menus memorized and the usuals identified. A well-worn path from my house to anywhere with a happy hour. But sometimes it’s more than a meal you’re craving. It’s nostalgia — even if it’s for a past you were not part of.

Leiper’s Fork is an unincorporated community that transforms from pass-through hamlet to a beacon of live music. Look for a halo of cedar-smoker plume hanging on the patio lights of Puckett’s and you’ll know you’ve arrived. I swear a cold beer here on a hot summer night with a cover band playing Sweet Caroline and you might as well be at the only place on earth. A new upscale BYOB restaurant in a historic house is a recent addition (highly recommend The 1892, by the way) and there’s even a spa next-door. Both are reminders that progress here is still homespun and folks might even pay a premium to keep it that way. Art galleries and knick-knacks catch the eye of the visitor, but if you grew up here, the whole place is only a reminder of the Christmas Parades, the Natchez Trace Pow-Wow, and Barney Fife’s Police Cruiser at the entrance to the village.

Leiper’s Fork Village

So on a Thursday in January, I made the forty-five minute drive down familiar two-land roads with a dear friend to settle in for a meal at The Country Boy. We’ve taken many drives like this together when the concrete of the urban core starts to feel like quick sand. And southerners aren’t good at late winter anyway. The only thing concrete at Country Boy is that the biscuits come to a hard stop by 11am and Miss. Debbie delivers cakes and pies every Wednesday and Friday. If they’ve got a slice of strawberry cake left, order it quick.

Lindsey is our server. She shows us to a table by the window and we immediately order both hot coffee and sweet tea. She rattles off the day’s specials from memory as another server greets a small table with a very rehearsed salutation of “What’s up, party people?” A cowboy in spurs walks in cooly and settles at the bar. The red and chrome swivel chair seems too small for his towering presence, but the chair holds and he orders a tea with a waive of his finger. A western playing on the TV above the bar steals his attention from there and the irony of the Marlboro man watching a western at The Country Boy is almost too perfect.

White beans are the special and I pair them with my catfish basket and side of fried okra. Lindsey smiles when she brings me a leftover biscuit from breakfast. Maybe it was because I mentioned I grew up here or maybe it was just leftover. Either way, it’s well over an hour past the 11am biscuit cutoff and I silently agree to not boast about it or hold them to the exception next time.

A table of men sit under a hanging wooden sign that reads “Grumpy Old Men.” It’s designated for them and them only. It is their sacred table. I feel a tinge of jealousy that I can’t be one of them and I catch myself from leaning too far in. Their stories are old-growth and worn with a familiar patina. There are no unknowns in the tall tales—it’s all family names and cousins. The gossip is recycled and recirculated in hushed tones until an eruption of laughter reminds you it’s the storyteller more than the story sometimes.

Reba McEntire walks in and sits at the table beside us. She’s wearing a buffalo motif button-down and orders the chicken salad sandwich. She gets treated like everybody else. Even gets the rehearsed “party people” welcome. A tourist that has nearly worn a hole in the menu with indecisiveness interrupts and approaches her table. She asks Reba for not one, but two different autographs. Until then everything at The Country Boy felt as it should—protected from the outside like it was 1968 where Old Hillsboro Road was just an approach to sprawling farm land instead of a destination for spotting celebrities.

We pay our tabs and walk silently past Reba. I hear Lindsey tell one of the Grumpy Old Men that he’s gonna drink them out of sweet tea when he rattles the ice in his plastic cup at her. It smells like diesel and cows when we walk outside and somehow it’s the perfect compliment to the fried food we’ve been immersed in.

Lunch at The Country Boy has only wet our whistle for more. We want to dig deeper, feel a little more connected, try and drive off the giant slice of chocolate pie we devoured. We head southwest to visit Fly’s General Store. It’s a delightful mess of hoarding for sale; tucked into a gravel gulley off Leiper’s Creek Road. It’s like your grandpa’s barn only everything’s for sale and you’re mighty thankful you won’t inherit the mess.

My heart sank when we read the handwritten note on the door: Closed. It was gone but not gone. Right there but untouchable. Another relic on the side of the road that had slipped out of our grasp. We shuffled gravel around in the cold for a while while it settled in. I think we both waited for someone to drive over in an ancient Ford F-150 and unlock the door. But nobody came and the place stays locked full of junk treasure.

If anything it reminded me why I’m drawn to these places: to preserve something, salvage a simpler existence. Fly’s being gone feels like a personal failure in a strange way. I was too late to walk those cluttered aisles one last time and cough at seventy years of dust in a way that I could remember well enough to retell. I didn’t get to write it all down.

It was a beautiful overcast day for a drive and we tried to not let the loss of Fly’s get to us. We turned back and pulled into Nett’s—relieved when the door opened and a two-top of locals turned to look at us from their lunch plates. An aluminum pie pan sat behind a glass case with two pieces missing.

“What’s this?” I asked, peering against the glare to inspect closer.

“Raisin pie,” the friendly clerk with a smoker’s voice answered. “You wanna piece?”

“We just had chocolate cake at lunch,” I admit, hand on my stomach.

She lowered her eyes and asks again, “So you wanna piece?”

How could I refuse? She serves me up a slice to-go and we pile a few other things on the counter—pre-packaged cookies for my son’s after-school snack and Coca-Cola’s in glass bottles. There’s a printed out and laminated sign hanging under the Skol dispenser saying “I can’t believe I work this hard to be this poor.”

I chat with the clerk for a while. Her name’s Casey and she tells me she always orders dessert first when she gets together with her family for their monthly dinners out. She tells me O’Charley lets you order pie before your supper if you like and Cherry is her favorite. She said her grown children give her a hard time about it. She looks at me and lowers her eyes again in a way that tells me she was a fantastic and terrifying mother. “I think I’m old enough to know when to eat my pie.”

I believe her. And I envy her.